I used to work during summers for a bricklayer. I learned one thing there: air conditioning is pretty good stuff. (We should do more of it.)

Some people think bricklaying would be a great job, kind of like playing Tetris all day, except with real blocks. But here's what the real reality is:

Pick up brick, apply mortar, place, tap down, remove excess mortar.

Pick up brick, apply mortar, place, tap down, remove excess mortar.

Pick up brick, apply mortar, place, tap down, remove excess mortar.

Row after row.

Wall after wall.

Job after job.

Until you die. Of the heat.

One day, I graduated and went to work as an electrical engineer. Big plus: air conditioning! (We should do more of it.) Big minus: there's a lot of high-tech bricklaying.

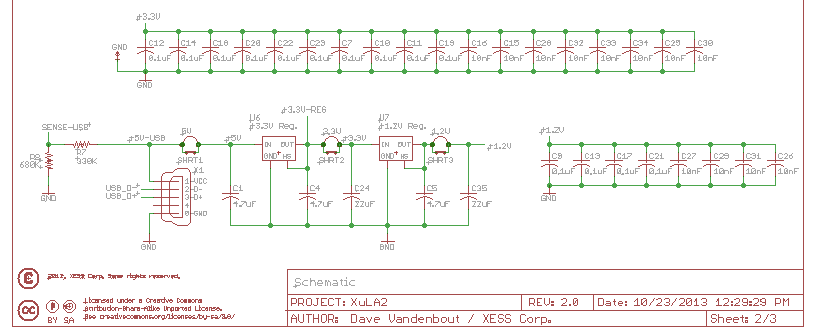

Case in point: bypass capacitors. Electronic components need these to smooth out the ripples and transients on their power supply inputs. A general rule-of-thumb is there should be one bypass cap for each ground pin on a chip. But there are chips nowadays that have hundreds of ground pins which means placing hundreds of bypass caps. Here's a section of a schematic showing just the bypass caps for a relatively small chip with around a dozen ground pins:

And here's the design process:

Click on capacitor symbol. Drag & drop. Attach power. Attach ground.

Click on capacitor symbol. Drag & drop. Attach power. Attach ground.

Click on capacitor symbol. Drag & drop. Attach power. Attach ground.

Part after part.

Page after page.

Design after design.

Until you die. Of boredom.

As I discovered with bricklaying, that's no way to live. This particular problem is caused by the manual nature of graphical schematic editors: they require the application of conscious thought to each repetition of common operations. Even if you use copy-paste to lay down multiple bypass caps, you're still repeating yourself. And each repetition is an opportunity for an error to creep in.

That's one reason I invented SKiDL, a programming language for creating schematics. Unlike GUI-based tools, programming languages are great at automating repetitive stuff. I'll demonstrate that by writing code that automatically adds the bypass capacitors to a chip.

Assume I have a chip with a bunch of ground pins, say twenty. With SKiDL, I could create the bypass caps like this:

from skidl import *

vdd = Net('+3.3V')

gnd = Net('GND')

bypcap1 = Part("Device", 'C', value='0.1uF', footprint='Capacitors_SMD:C_0603')

bypcap1[1,2] += vdd, gnd

bypcap2 = Part("Device", 'C', value='0.1uF', footprint='Capacitors_SMD:C_0603')

bypcap2[1,2] += vdd, gnd

...

bypcap19 = Part("Device", 'C', value='0.1uF', footprint='Capacitors_SMD:C_0603')

bypcap19[1,2] += vdd, gnd

bypcap20 = Part("Device", 'C', value='0.1uF', footprint='Capacitors_SMD:C_0603')

bypcap20[1,2] += vdd, gnd

Servicable, but not very readable. Let's recast it as a loop:

from skidl import *

vdd = Net('+3.3V')

gnd = Net('GND')

for _ in range(20):

bypcap = Part("Device", 'C', value='0.1uF', footprint='Capacitors_SMD:C_0603')

bypcap[1,2] += vdd, gnd

That little for loop will instantiate twenty caps and connect each one to power and ground.

Boom! Easy.

Easy, but not very general. I have to know how many ground pins there are on the chip and then write a loop. Too much work; SKiDL should figure that out for me. How about if SKiDL counts the number of ground pins on a chip and uses that to set the loop bound like this:

from skidl import *

vdd = Net('+3.3V')

gnd = Net('GND')

fpga = Part('xilinx', 'XC3S200AN/FT256') # Create a XILINX FPGA.

num_gnd_pins = len(fpga['GND']) # Get a list of ground pins and count them.

for _ in range(num_gnd_pins):

bypcap = Part("Device", 'C', value='0.1uF', footprint='Capacitors_SMD:C_0603')

bypcap[1,2] += vdd, gnd

Better, but I really don't want to type out that loop for every chip that needs bypass caps. Luckily, programming languages have functions to encapsulate code that's used multiple times. SKiDL is a programming language, so it must have them too! Let's encapsulate the bypass cap instantiation loop in one:

from skidl import *

def add_bypass_caps(chip, vdd, gnd):

'''Add bypass capacitors between vdd and gnd to a chip, one for each ground pin.'''

num_gnd_pins = len(chip['GND'])

for _ in range(num_gnd_pins):

bypcap = Part("Device", 'C', value='0.1uF', footprint='Capacitors_SMD:C_0603')

bypcap[1,2] += vdd, gnd

vdd = Net('+3.3V')

gnd = Net('GND')

fpga = Part('xilinx', 'XC3S200AN/FT256')

add_bypass_caps(fpga, vdd, gnd) # Call function to add the bypass caps.

That's good; now all that's needed is a function call.

But maybe I don't want to do even that much.

Instead, I could create a subclass of the Part class that adds the bypass caps

when I first instantiate the chip:

from skidl import *

def add_bypass_caps(chip, vdd, gnd):

'''Add bypass capacitors between vdd and gnd to a chip, one for each ground pin.'''

num_gnd_pins = len(chip['GND'])

for _ in range(num_gnd_pins):

bypcap = Part("Device", 'C', value='0.1uF', footprint='Capacitors_SMD:C_0603')

bypcap[1,2] += vdd, gnd

class PartWithBypassCaps(Part):

'''A subclass of Part that adds bypass caps to the part that's created.'''

def __init__(self, *args, vdd, gnd, **kwargs):

Part.__init__(self, *args, **kwargs) # Normal part creation.

add_bypass_caps(self, vdd, gnd) # Add bypass caps.

vdd = Net('+3.3V')

gnd = Net('GND')

# Instantiate the chip and also get all the bypass caps automatically.

fpga = PartWithBypassCaps('xilinx', 'XC3S200AN/FT256', gnd=gnd, vdd=vdd)

So I've gone from explicitly instantiating each bypass capacitor, to using a loop, then a function, and finally ended up with a class that adds the caps implicitly. And that class can be used for chip after chip in design after design until I die. But not of boredom!

Are there shortcomings in my technique? Of course (and I'll correct them in a future blog post), but I wanted to keep the code simple so it wouldn't distract from the primary point of using SKiDL:

Automation is pretty good stuff. (We should do more of it.)